I recently had this article published in Radix Magazine.

I am an artist living and working in Oakland, California. I live in a 100+-year-old house on a street of old houses lined with dying magnolia trees. My children have grown and left home, although the lure of dinner and the washing machine can entice them back. We have an extra bedroom that we share with a stream of young adults in transition. The latest, a young sailor, sometimes needs a place to anchor when she is studying for her captain’s license, or her money has run out, or she is recovering from a broken heart.

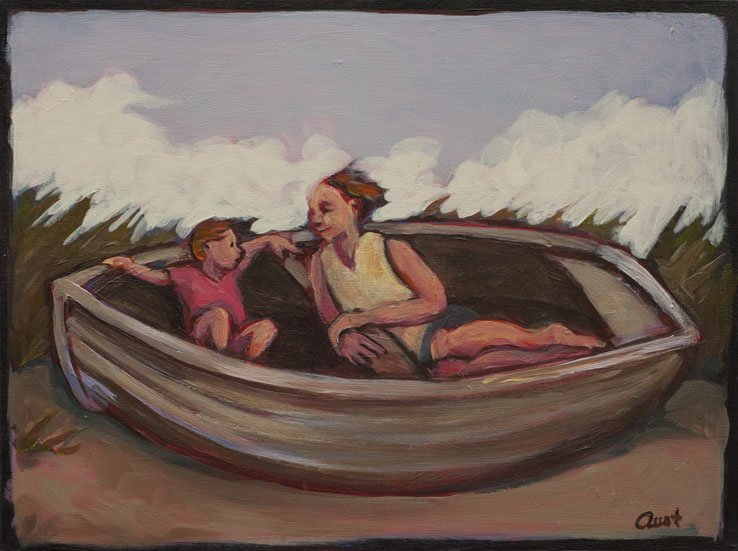

So I paint a woman in a boat on a beach, hands open, no oars. The painting is my prayer for our sailor as she embarks again. Many of my paintings begin as prayers.

Open Hand, acrylics on canvas, 60″x30″

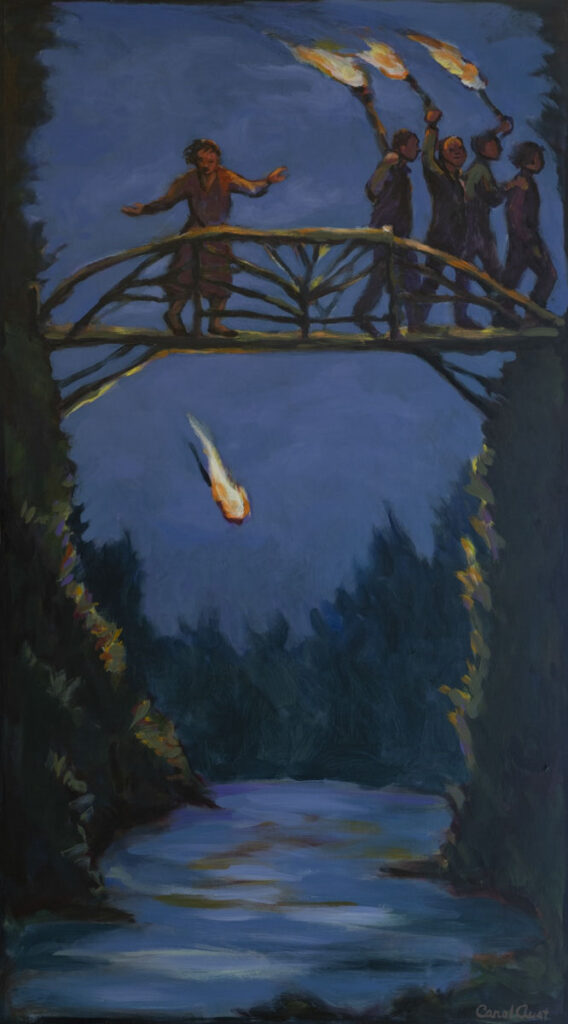

I paint a bridge across a canyon. I paint a woman on the bridge, arms open, eyes averted. It feels too passive, not right. I cover the woman with blue. I paint a woman striding forward. I don’t like that either. I paint a woman dropping her torch behind a night procession. My prayer is that the young adults in my life, my children and my guests, learn to separate from the world’s pressures when they need to.

Bridge in Torchlight, acrylics on panel, 45″x25″

Every afternoon I descend to the basement of my old house, a cup of tea in one hand, a plastic water carton with brushes in the other, to where my studio waits under old redwood beams that creak and moan during occasional earthquakes. Going down to the basement is like descending into my subconscious. In the big dim subterranean space, the lights focus on an easel. When I paint, I become completely absorbed. I step back and look at what I’ve painted, and then I move in close to paint more. The hours fly by.

To counterbalance my studio solitude I volunteer as a tutor with children and young adults, teaching them how to read. Unaccompanied minors, unhoused youth, teen moms from Yemen—it takes a miracle for them to learn how to decipher the words on a page.

Later in the day, I put another panel on my easel and paint a mother and child, another prayer. As I paint it, I put my students in God’s arms. I rest in God’s arms, too.

Mother and Child #48, acrylics on panel, 14″x14″

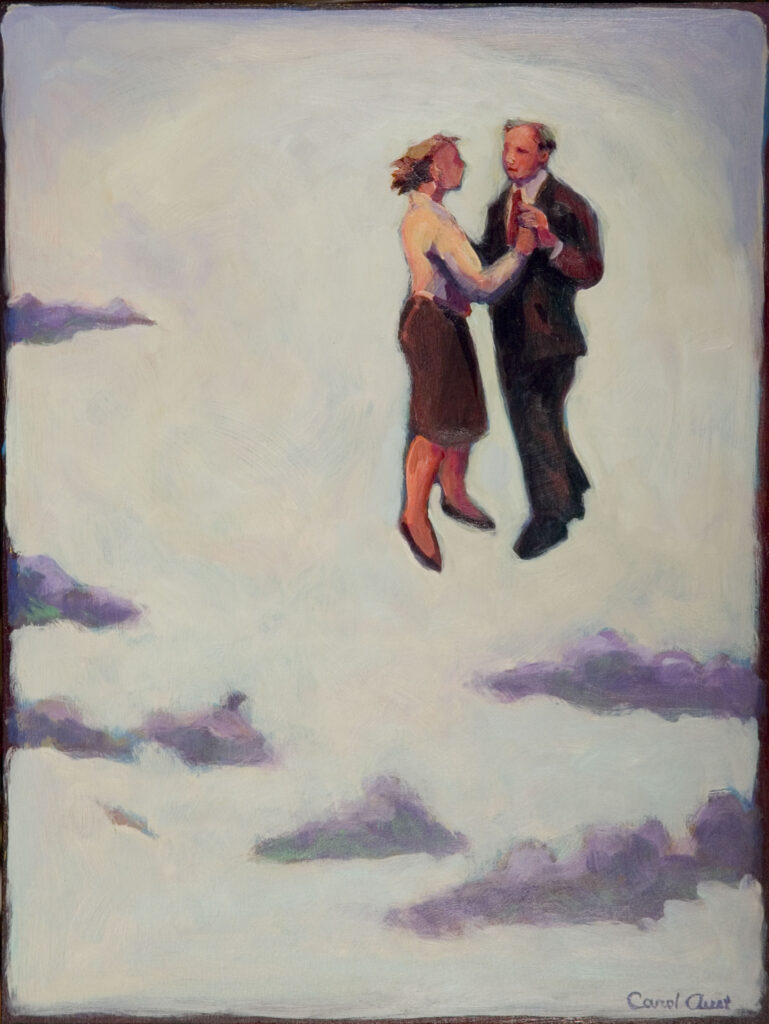

There’s a second chapter to the paintings I make. Creating art is like raising children, and just as leaving home is a process, a painting isn’t necessarily finished once I sign the corner. In fact, its life has just begun. When a painting leaves my studio and elicits responses from viewers, the art becomes a living force in the world. Viewers of my work add the next chapter to the unfinished story, explaining why the woman is traveling alone, why the couple is dancing in the clouds, why the party is being held in the desert, what the particular painting means to them.

Years ago I painted a couple dancing and floating high among lavender clouds. I titled it No Visible Means of Support and hung it at an open studio. A couple approached me, and the wife said, “We need to have that painting,” gesturing to the dancers. I smiled and reached for my invoice book, but she stopped me and explained, “No, we really need that painting.” So I put the invoice book down and leaned in. She put an arm around her husband. “Mark had cancer this year and we had no visible means of support.” The painting changed and deepened at that moment; it became an instrument of healing.

No Visible Means of Support, acrylics on panel

Another time, a woman called me and said, “I want to buy Out the Window, but you’ll need to deliver it to me because I’m in hospice.” I took the painting to a brown bungalow in the East Bay Hills, and someone led me to the living room where the woman who called me was reclining on a sofa. I rested the painting against an armchair, and we sat and looked at it together. It depicted a woman in a blue room, floating out of a window into a white sky. The woman said quietly, “My grandfather died by jumping out of a window after he returned from the war.” I paused and asked her if she wanted me to take it away. She answered, “No. I always thought that when I died I’d go into darkness, but as I look at this I realize I’ll go into light.”

Three weeks later, her friend called me and told me that the woman had died. I offered to take the painting back, but she said, “No, her husband wants to keep it. It comforts him.”

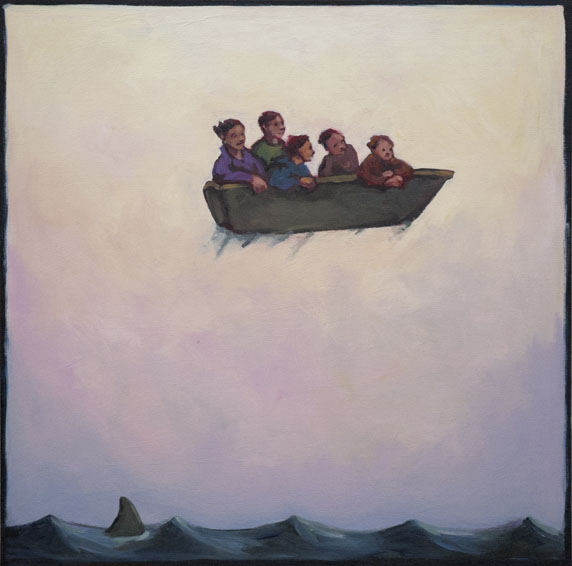

A few months later, a gallery director took some art of mine to a potential client, including a painting of a woman and four children in a flying boat. As she unloaded them in the client’s driveway, the woman gasped and explained that her husband had died suddenly a few years before, leaving her with four children and a large company to run. She took the painting and hung it in her bedroom in order to focus on the strength of the woman in the boat.

No Worries, acrylics on panel, 24″x24″

Often, I don’t hear the stories; I just see the tears. People will apologize as they dab their eyes and say, “I don’t know why I’m crying.” and I’ll respond, “That’s okay. It happens.” I know the art is touching a nerve, bypassing a wall they’ve erected.

A member of my church bought one of my paintings of a mother hugging a girl at an auction. The next Sunday she explained through tears, “My mother died when I was eight. When I look at that painting I feel like God is holding me.”

Forest Hug, acrylics on canvas, 18″x18″

A woman wiped tears as she looked at Tell Me All About It, a picture of a mother listening intently to her child. “My mother listened to me like that,” she explained, and then paused and went on. “I just realized that today is the anniversary of her death.”

Tell Me All About It, acrylics on wood panel, 9″x12″

As an artist, I approach the canvas humbly and honestly. There’s no formula to follow. I’m not consciously trying to evoke emotions in the viewer, and I can never predict what paintings will touch people. Sometimes a piece of art will be unnoticed for years but then hit someone very miraculously. All I know is that if I’m faithful to God in painting my deepest truth, sometimes God uses the art to speak to people. The invisible becomes visible in a way that bypasses language. There’s a mystery here that I don’t understand.

In the dining room of our old house, I often extended the table by wedging an artist panel in the middle. For the five years before Covid, we would unlock our front door every Wednesday evening and put on a big pot of soup or a casserole, and fifteen to twenty-five friends (and an occasional delivery person) would come and dish up, laughing, arguing, and pushing their chairs back to make room as more guests arrived. It feels like a dim memory now. When the pandemic swept through our city and overflowed our hospitals, we kept our doors locked. I begin a new canvas, a canopy of trees with a golden opening in the distance. But what should I put in that archway moving towards the future? I paint a solitary woman carrying a suitcase. But I’ve painted her too many times these past years, so I cover her with pink. I paint a solitary woman on a bicycle, but I paint over her, too. I become so frustrated that I put the canvas away, facing the wall. I feel like a failure, like I’ll never paint anything good again.

I wait a couple of weeks and pull it out, and then the miracle happens again. I paint a gathering of friends with suitcases piled nearby—not a big group, but one that’s beginning. It’s good enough, and I feel deep relief. But then I have to throw down my brush and run upstairs to start the soup. People are arriving for dinner soon.

Come As You Are, acrylics on canvas, 36″x36″

No comments:

Post a Comment